Politics in Comics: Mr. A

Conservatism seems to be a difficult topic for comics to deal with, especially for traditional superhero comics. Part of that could stem from the medium’s early liberalism (While Superman is considered a conservative character nowadays, his early adventures usually had him taking on wealthy corporate crooks and greedheads), but in general, most comics writers just seem to have trouble tying characters to political views. Even characters whose conservatism is considered well-established often have fairly vague political beliefs — how do we know, for example, that Hawkman is a conservative? Is it because he’s in favor of lower taxes or opposes gay marriage? No, it’s because he always gets into big arguments with Green Arrow, who is a liberal.

But sometimes, a creator comes up with a compelling character whose conservative political philosophy is not just specifically stated, but is an intrinsic part of the character’s personality. For instance: Steve Ditko’s Mr. A.

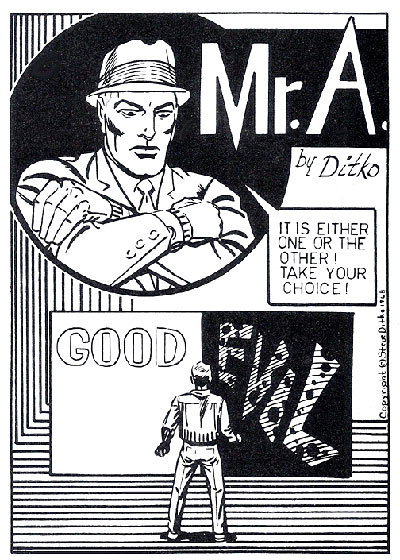

Ditko, of course, is the co-creator of Spider-Man, Dr. Strange, the Creeper, Captain Atom, and dozens of other characters. But he’s had a bit of a snarky relationship with comics — he hasn’t given interviews or made personal appearances since the ’60s, and his general dissatisfaction with the current state of the comics industry is pretty well-known. Ditko is also a follower of author Ayn Rand’s conservative philosophy of Objectivism, and in 1967, he decided to create a hero embodying Objectivist principles.

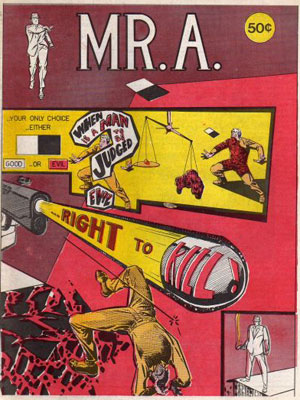

The result, in the third issue of “witzend” magazine, was Mr. A. Named for the Randian “A is A” philosophy of the “Law of Identity,” Mr. A was really reporter Rex Graine. He never really had an origin — he just went out in his all-white suit and fedora and his solid steel mask and gloves, and fought crime. He leaves business cards that are half white and half black to signify his belief that there is only good and evil, with no moral gray space in the middle.

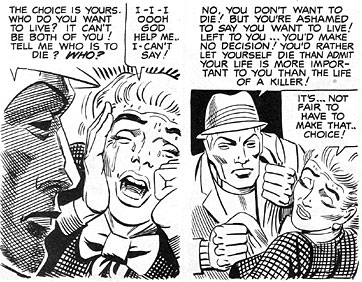

The typical Mr. A story focused on a character who convinces himself that he can do a small number of illegal acts without compromising his own inherent good nature. But those small crimes eventually snowball into larger and more serious crimes. They often try to justify their actions by blaming other people, the environment, or society for their own actions. People who commit only small crimes may only be delivered by Mr. A to the police for trial, but murderers are often left in a position where they must rely on Mr. A to save them, and he never lifts a finger to save the guilty, because they never lifted a finger to save the innocent.

Of course, Mr. A is indeed impossibly merciless, but that’s been done plenty often before. Mr. A wasn’t really written in order to be realistic or to be a thrilling adventure tale — its primary purpose is to promote Objectivism. Does it do that job well? On the one hand, there’s not much way to doubt that Mr. A is as close as you’re going to get to an Ultimate Objectivist — he never compromises or bends his principles; he absolutely does not believe that evil is subjective; he’s a moral, intellectual and physical super-specimen, especially compared to most other people; and he’s a really, really preachy guy.

The big problem for Mr. A as a piece of Objectivist propaganda is that the only people who think Mr. A is an appealing role model are people who are already Objectivists. You wouldn’t want to hang out with a guy like Mr. A, getting all scowly and condemnatory if your favorite football team got too many penalties. You wouldn’t even want him to be a cop, ’cause he’s the type of guy who’d haul you off to jail for jaywalking. You wouldn’t want to hang out with Mr. A, and there probably aren’t too many folks who’d want to be him, either.

But “Mr. A” is still a series and a character that I feel a lot of respect for. He’s a well-realized character with conservative beliefs that don’t derive from whatever the latest shouting points are on right-wing thug radio, or devolve into cartoonish parody. And besides that, Ditko’s artwork is fun to look at, too. 🙂

And of course, Mr. A is closely related to another Ditko character, the Question, who got his start very close to the same time as Mr. A. Originally a Charlton Comics character, the Question was another vengeful Objectivist, though it’s been a few decades since the Question was portrayed that way. And Mr. A also has ties to Rorschach, the uncompromisingly conservative vigilante who co-starred in Alan Moore’s “Watchmen” series in the mid-1980s.

(For more on Ditko and Mr. A, be sure to read Dial B for Blog’s Mr. A series.)