The Pumpkin King with His Skeleton Grin

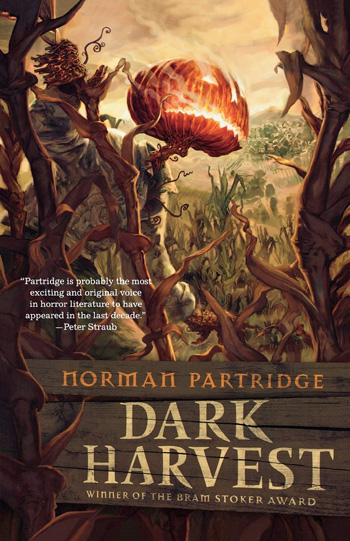

My children, tomorrow is the best day of the year, and I still have time to review another horror tale. Let’s look at one of the best Halloween stories out there, Dark Harvest by Norman Partridge.

Well, here we are — it’s Halloween night, 1963, in the little podunk Midwestern town you call home, and it’s time for the biggest event of the year. But it’s not trick-or-treating. It’s not the Halloween parade. It’s the time when the October Boy, Sawtooth Jack himself, that pumpkin-headed, candy-stuffed, butcher knife-wielding scarecrow, hauls himself out of the cornfield and makes his way toward town. And if he makes it to the church before midnight, there’s going to be big trouble.

Luckily, every teenaged boy in town is in the way, armed with clubs and machetes and kitchen knives and pump handles and more. Why just the kids? Because the only way anyone gets to leave this little podunk Midwestern town you call home is to kill the October Boy before midnight. Seriously. The lucky kid gets permission to go live his life outside of this little hellhole, and the rest of you are stuck here forever. So get after it, kid. You don’t wanna be on the wrong end of the knife when you’re staring down Sawtooth Jack’s crooked grin.

Much of our story focuses on 16-year-old Pete McCormick, on his first year going after the October Boy. He’s a smart kid, smarter than most — he knows he can’t rely on brute strength and bravado to take down a nightmare with a pumpkin’s face — but like almost every other kid in town, he’s stuffed full of resentment and anger. He’s been stuck in this town his whole life, watching his drunkard father get beat down and knowing that’s the best he has to look forward to — unless he can make his escape.

But the October Boy isn’t the only obstacle Pete has to contend with. There’s every other teenaged boy in town, many of them stronger and more violent than he is. There’s Jerry Ricks, the brutal, thuggish cop who’s run the town as long as anyone can remember. And there’s Kelly Haines, the only girl participating in the competition, the person who knows all the secret scandals Pete hasn’t learned about yet.

Will Pete get his free trip out of town? Or will the October Boy drag the town to Hell with him?

Verdict: Thumbs up. This is a thoroughly fun book, though I hesitate to classify it as straight horror. Yeah, it’s got a pumpkin-headed scarecrow, multiple murders, a conspiracy stretching back generations, and evil both supernatural and mundane, but it feels more like a hardboiled crime novel than anything else.

A lot of Norman Patridge’s writing is in detective fiction, and his writing style in this book is picture-perfect crime noir. Almost everyone in the book is at least a little bit sleazy — the first thing the hero does on Halloween night is break into a cop’s house to steal his gun, after all. And the book is stuffed to the gills with performative machismo. I don’t even consider that a bad thing! Desperate, violent men doing desperate, violent things to other desperate, violent men is one of the best ways to write hardboiled crime fiction. And yes, Kelly Haines, essentially the only female character in the book, does manage to clock her share of dudes upside the head with a brakeman’s club, but as much fun as she is, as much as she moves the story along, she won’t be mistaken for the main character.

And the main character, by the way? It’s actually a pumpkin. Because we do spend about half the story’s length inside the October Boy’s blazing brain as he’s constructed in a cornfield, his wooden chest cavity stuffed full of candy, as he plots his way through the night, as he remembers his past, as he decides what kind of creature he’s going to be. It’s his desire for revenge that drives the story forward, it’s his decisions and planning that change the town’s fate, and it’s his ability to show mercy that brings the tale to its proper conclusion.

“Dark Harvest” was nominated for a World Fantasy Award and an International Horror Guild Award in 2007, and it won the Bram Stoker Award for Best Long Fiction in 2006. Publishers Weekly picked it as one of their 100 Best Books of 2006. So it’s not just my opinion, y’all — it’s a great Halloween story, and you should go look for it, read it, and remember what it’s like to run the streets of your hometown with a baseball bat, looking for your showdown with the October Boy.

Comments off