The Elephant Remembers

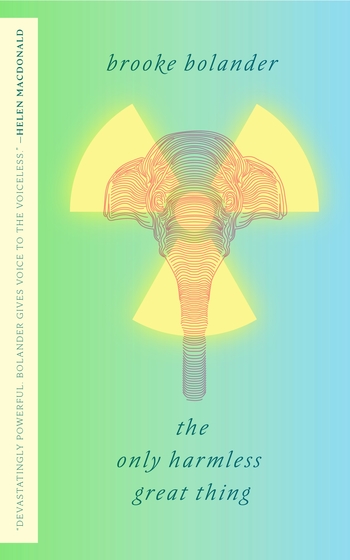

Feels like it’s past time for me to do a book review, so let’s look at a short one — namely, The Only Harmless Great Thing by Brooke Bolander, a novella about radiation, elephants, storytelling, and rage in the face of injustice and cruelty.

This story has roots in two incidents from real-world history. The first is the Radium Girls, female factory workers who painted radium on watches in the 1910s and ’20s. Glow-in-the-dark watches were a minor craze, and the workers’ employers suggested they use their lips to twist their paintbrushes to a fine point while painting. The workers also painted their fingernails and teeth with radium, for that fashionable glow-in-the-dark look. But it turns out that radium is actually dangerously radioactive, and many of the workers got sick and died from jaw and mouth cancer. Courts and corporations were slow to react, and by the time justice was done and worker safety regulations were in place, the workers who had been sick had mostly already died.

The second incident from history that was used for the story was the death of Topsy the Elephant in 1903. She was an Indian elephant at a circus who got a reputation as a dangerous animal, mainly because she’d been very cruelly abused by her drunken handler, and in fact, by mostly everyone else around her, and she got sick of it, and she occasionally lashed out. She did kill people, but no one really knows how many. But her new owners at the Luna Park amusement park decided they were going to put on a special show and execute her. They wanted to hang her from a giant gallows, but the ASPCA said it was too much. So they poisoned her, electrocuted her, and strangled her with a steam-powered winch. It was long believed she was killed as a demonstration by Thomas Edison of the power of electricity, but in fact, this was 20 years after the so-called Electricity Wars, and the lone Edison connection was the Edison cameras that filmed her death.

So Brooke Bolander took these two incidents, and she made a story that brought them together and gave them a little justice.

This is set in an alternate history, and the biggest difference between our world and the world of the book is that elephants are at least as intelligent as humans, and everyone knows it — and it doesn’t really make a big difference in how they’re treated. Instead of being abused because they’re big dumb animals, they’re abused because they’re big smart animals. The tale flip-flops back and forth in time, from prehistory, to the late 1910s, to the present day. But the way of the elephant is always hard.

The bulk of the story, the most important part, takes place in the ’10s. Much of our focus is on Regan, a former factory worker, one of the Radium Girls, now eaten up with cancer. But to earn some extra money for her family after she’s gone, she’s agreed to use her sign language skills to teach elephants how to do the job she used to do, painting radium on watch faces. Yeah, the radium will kill the elephants, too — but they’re bigger, they can take more of the radiation, they’ll live longer. That’s all US Radium cares about.

So Regan spends her days with Topsy, the infamous killer elephant, signing back and forth to each other. Topsy can tell Regan is dying, and she tolerates her about as well as she tolerates any humans. And when a thuggish manager decides to release his frustrations on the sick kid who can’t fight back, Topsy effortlessly and joyfully tears him to pieces. And US Radium decides they need to give her a big, public execution. Something with some flash, with some flair, something with… electricity! And Regan figures out a way to get revenge on everything, for both of them. And all it’ll take is a little hidden vial of volatile, radioactive goo hidden in an elephant’s cheek, waiting for a short sharp shock.

And the world changes. And it doesn’t change.

Verdict: Thumbs up. There are a number of reasons you’re going to want to read this, and very high on the list is going to be the extremely high quality of the writing, which is excellent when focused on Kat, our P.O.V. character in the present day, and even better than that when we’re inside Regan’s head in the 1910s — her frustration, pain, sickness, sorrow, yearning, and desire for justice or at least vengeance are painted radioactively on the page — you can’t help but get infected.

But the book really hits its highest points when we have a focus on Topsy or on the ancient myths of the elephants. They are by far the most poetic sequences, and they allow us to see the strange, alien ways that elephants think, as well as the ways they still share what we’d think of as human emotions. Elephants have long, powerful memories, and they tell their history through stories that are repeated from mother to daughter throughout the generations. They are also a matriarchal society, with mothers and grandmothers prized most highly, but aunts, nieces, cousins, and daughters also of great importance. Male elephants are pitied, disliked, and avoided — and since they tend to wander by themselves away from the herds, no one seems to mind. Elephants communicate with each other in ways humans can’t perceive, and they see us as loud, aggressive, fearful, foolish, frail creatures.

There are also interesting ways in which Regan and Topsy share a sisterhood. While Regan isn’t responsible for Topsy’s captivity or the decision to expose her to radium, she is tasked with teaching her how to paint watch faces. They’re both poisoned by radioactive material, and they both have some violent tendencies — Topsy has killed humans multiple times, while Regan tweaks Topsy’s ears when she’s frustrated with her. And Topsy may get the full credit from the public for her own destructive end, but it would not have been possible without Regan’s planning and her secret radioactive vial.

A major theme of the book is the quest for justice for the oppressed — particularly the rights of workers, animal rights, and women’s rights. The situation wasn’t good on any front in the 1910s, and in a lot of ways, we’ve had a rough period of backsliding in recent years. The lesson Bolander offers for the oppressed is essentially “Seek out allies, even in unexpected places, and offer your support.” (And a secondary theme: “Sharing our stories brings us strength.”) The message for oppressors is also crystal clear: “If you stand in the way of justice, don’t be surprised when the people take revenge.”

If the book has a weakness, it’s that all the flips backwards and forwards in time can get confusing — but I also think the tale is told best through the multiple time periods. It’s also not a long book — I expected a fairly significant novel when I bought it, but the entire story is less than 100 pages long. But it’s still worth buying, reading, and loving. Go pick it up.