Happy Birthday, Clifford Simak!

Hey, I noticed that today is the birthday of Clifford D. Simak, science fiction grandmaster and one of my favorite writers. Let’s take a look at his very best book — City.

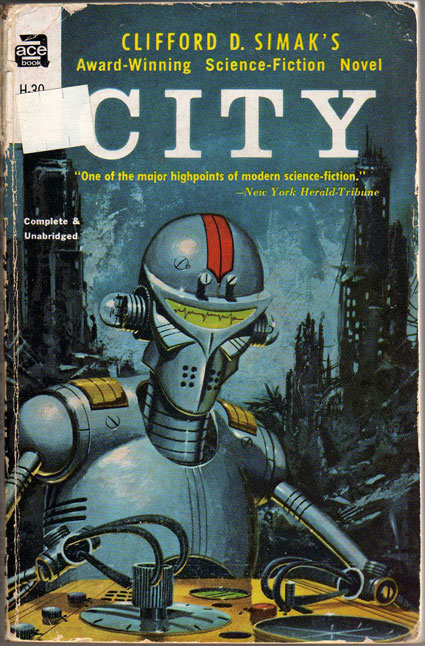

(FYI, that’s a scan of the first copy of this book I ever got, and it’s still my favorite because I love the retro sci-fi cool this cover is drenched in…)

This is the kind of story that exemplifies why I love so many stories from science fiction’s Golden Age — it has stereotypical sci-fi elements like robots, mutants, and aliens, it has completely unscientific elements like talking dogs and intelligent ants, it has wild, breathtaking ideas, it has characters you can’t help but love and hate, and its glimpse of the future is simultaneously grim and hopeful. It’s far from a perfect book — there are ongoing assumptions in the story that most of humanity, regardless of cultural differences, will always speak and act with one voice. There are no important female characters in the whole book. And some of the science is distractingly goofy. Nevertheless, Simak is one of science fiction’s unrecognized geniuses, and this is his masterwork.

“City” is the story of how mankind dies, told from the perspective of the intelligent dogs who have taken over the Earth in our absence. It’s all framed as an attempt by the dogs to assemble an oral history of the planet, including the improbable myths of a creature called Man that used to run things in the distant past. Much of that history follows the lives of a single human family, the Websters, and a nearly immortal robot named Jenkins.

In the initial story, told only a short distance in our own future, humanity is in the process of abandoning all of its cities. Mostly plotless, it serves mainly to allow us to follow the transition from today’s urban society to a future society using advanced technology to embrace a more pastoral lifestyle. Technological advances in transportation and communications have rendered the city unnecessary — people can live anywhere they want and still stay in contact with their friends, families, and coworkers. Anyone can feed themselves with a hydroponic garden. Few people want to live in big, crowded, smelly cities, which are mostly abandoned except for some squatters. Only a few old-timers still cling to the old ways.

A century later, we get to our first really important character, Jerome Webster, a doctor who’s been turned into an agoraphobic, terrified of open spaces, by his comfortable life at home. His every need is taken care of instantly by the family’s robots, including the butler, Jenkins. Webster is called upon to travel to Mars, where history’s greatest philosopher, Juwain, is gravely ill — if he lives, he will soon develop a new philosophy that will propel humanity to the very peaks of perfect enlightenment. But Webster finds himself completely unable to undertake the journey to save his friend.

We jump forward several decades and sees the introduction of the Dogs, as Jerome Webster’s grandson surgically gives his pet the ability to speak. We also meet Joe, a mutant who is able to live for centuries and is gifted with extraordinary intelligence. A completely amoral creature, he has spent over a hundred years helping humans, but he’s getting bored with that. So he steals the last notes on Juwain’s revolutionary Martian philosophy, just for the pleasure of hurting humanity. We also get our first look at the ants, as Joe puts a nest on the path to higher intelligence by protecting it for a few winters, then sadistically demolishes the mound. But the ants have already learned quite a bit, and they’ll be back…

The years march on, and we leave Earth to visit the hostile surface of Jupiter, where scientists have attempted to explore the planet by transforming themselves into creatures that can survive the corrosive atmosphere — but none of these scientists have ever returned. What predator could be killing them off?

Decades, centuries, millennia pass. The Webster family continues on, slowly dooming the human race with each decision it makes. The Dogs continue on, growing in sophistication and morality. Jenkins and the other robots continue on, shepherding the new animal civilization through the years. The ants continue on, becoming more and more powerful. Some species die off, some species evolve into new forms, some species abandon Earth forever. Life continues, on and on. Earth continues.

Verdict: Thumbs up. No question, it’s a melancholy, almost heart-breaking story. If you’ve long dreamed that mankind would live forever, this story will subject you to the spectre of the human race embracing extinction, of humanity’s greatest works of science and art being forgotten, of even Man’s Best Friend leaving our home planet behind in the face of an expansionist alien species. Simak’s “Epilog” (which is not present in all editions of the novel) is even sadder. “City” is a book with few truly happy endings.

And yet, I still see this as a hopeful book, and it fills me with joy when I read it. Perhaps it’s the beauty of the writing and of the story. Perhaps it’s the fact that many of mankind’s creations — robots, dogs, storytelling, morality and ethics — continue thousands of years beyond our end, even if our status as the creators are long forgotten. Maybe I just really like dogs.

Maybe I enjoy the novel so much because I like the way it’s acknowledged that, eventually, all species must die out — extinction is inevitable, but I think Simak knew that our story isn’t finished yet. Enjoy the good things that humanity has brought about, recognize the bad things that we’ve caused, resolve to help move the species farther along the evolutionary chain, scientifically, artistically, socially.

In the end, I think it’s a story about life and death and memory. Years will pass, centuries will pass. We will die, and those who follow us will remember us for a while. But we will eventually be forgotten. That thought may make you feel depressed and melancholy. But life, in some form, continues, and where there’s life, there’s hope.