The Creeping Terror

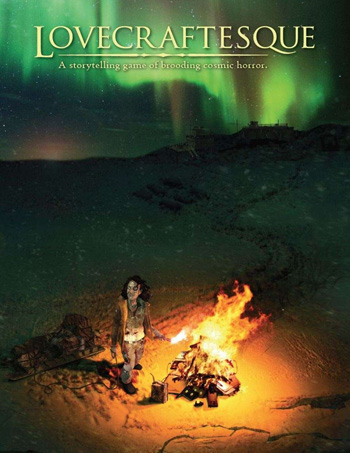

We’ve talked fairly recently about the need for horror and cosmic horror to move past H.P. Lovecraft and his racism, and it turns out there’s a roleplaying game that decided to figure out how to work that out. Can you have meaningful cosmic horror that doesn’t rely on Lovecraft and his creations to work? Let’s take a look at Lovecraftesque, designed by Joshua Fox and Becky Annison.

First of all, this isn’t your standard RPG, with players throwing dice to defeat monsters and steal all the gold in the dungeon. There are no dice and no GM. It’s a storytelling game, less reliant on the random roll of the dice and more focused on collaboratively building a cohesive, satisfying story.

And this game has some significant differences from its most obvious inspiration, the classic horror RPG “Call of Cthulhu.” Players are encouraged not to use familiar foes from the Cthulhu Mythos — no deep ones, no mi-go, no King in Yellow, no Nyarlathotep, not even Cthulhu itself. The name of the game, after all, is “Lovecraftesque,” not “Slavishly Recreating Lovecraft’s Works.” This allows the players to be surprised by the terrors they conjure up themselves, rather than confronting the same monsters every player has grown accustomed to over the years.

The other difference from “Call of Cthulhu” is more controversial among certain sets of performatively assholish players. “Lovecraftesque” advises players on ways to avoid the issues that made Lovecraft’s fiction so problematic. It’s a game that says no to racism, sexism, and homophobia, and even counsels players on how to avoid harmful and untrue stereotypes about mental illness. The game even offers a tool called the X-Card, which allows a player to veto a just-introduced story element they find unpleasantly upsetting or overwhelming.

So how’s the game work?

Every player cycles between three different roles: the Witness (who plays the main character), the Narrator (who describes the action and reveals clues), and the Watchers (any other players — they support the Narrator by helping to add details to descriptions and by playing some NPCs). These roles rotate from one scene to the next.

These scenes themselves have a specific structure of their own, with the game divided into three parts. Part One is five scenes long, and Part Two can be up to three scenes long. Each scene ends with the revelation of a new clue into the strange horror menacing the Witness. Part Three starts with a “Journey into Darkness” in which the Witness is taken, willingly or not, to the location of the final confrontation. After that, the “Final Horror” scene unveils the, um, final horror, and then an Epilogue reveals what happens afterwards. The Witness does not have to die, and may even survive entirely unharmed.

There are a number of special cards that allow the game’s rules to be broken in various ways, sometimes by letting a player take over as the Narrator or Witness, sometimes by introducing new story elements or clues, sometimes by forcing an ongoing effect that must be used through the rest of the story.

Another fun rule requires the players to “Leap to Conclusions” after every scene. Each player has to look at the available clues and plot points and put together their best guess as to what the Final Horror may actually be. These guesses will mostly be completely inaccurate, but they can give players some ideas about where they’d like to steer the story, and they’re fun to review once the game is over.

Verdict: Thumbs up. I know this all sounds fairly daunting, but plenty of advice is offered on how to set up and conclude scenes, how to create and develop the Witness, and how to bring the game to a satisfying conclusion. A full teaching guide is also included, which allows the rules to be quickly communicated to an entire gaming group.

Plus there are also over a dozen scenarios offered for players to use, complete with details about the Witness, some useful NPCs, settings, special cards to use, and sample clues for players who need some more ideas. The scenarios are from a wide variety of times and places, from the familiar 1930s New England to modern-day America, World War II London, the Deep South in the 1960s, a Russian ship trapped in polar ice in 1902, a spaceship in the distant future, pre-colonization West Africa, fraternity row at a university in the Midwest, a deep sea exploration base, and many more.

(Personal favorite scenarios: a house-sitter discovering bizarre hints of the eldritch in the memorabilia inside a ritzy Hollywood mansion; a cyberpunk scientist battling a computer virus that’s somehow adapted to infect humans; and a blind occultist researching a recently-discovered Braille edition of the Necronomicon.)

A couple essays are also devoted to advice for players on how to avoid problematic areas common to Lovecraft’s fiction. The advice on racism is likely the most vital — because Lovecraft was really racist, y’all — while also acknowledging the difficulty of avoiding racist tropes in many settings. If the Witness is a black man living in Jim Crow-era Mississippi, racism is everywhere. But if you come to a game to escape from the racism of the real world, in-game racism can make the game deeply un-fun. Still, the advice is sound, straightforward, and useful — find out what the other players’ comfort levels are with depictions of racism, avoid the common racist plotlines (like humans mating with subhumans — Innsmouth stories are popular, but they were based around Lovecraft’s fear of race-mixing), don’t make a whole race of people into diabolical cultists, and when it comes to creating villains, punch up, not down.

As for mental illness, one’s initial thought may be, “Is there anything left of Lovecraft and cosmic horror if you take out getting driven mad by the shocking revelations?” But as the authors point out, lots of people have mental illnesses, of different types and varying degrees, and very few of them are down with the idea that having an illness makes them prone to carving up sacrifices, joining cults, and summoning monster-gods from beyond strange aeons. Besides a lot of Lovecraft’s “madmen” were either entirely lucid and not actually insane, were only affected for a short period of time, or were likely suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder.

So the authors’ advice is to be aware of what your players will be uncomfortable with, and to be mindful of how you’re depicting mental illness. They also suggest describing symptoms of a breakdown — it’s possible that everyone who encounters the quad-dimensional hellbeasts from the Bile Realms suffers mental trauma, but they can all have unique symptoms, tailored to their existing personality. A soldier could become hyper-vigilant or obsessed with cleaning her weapons; a professor could try to track down all information about the horrors or retreat from learning completely; or any of a very wide array of symptoms could develop. Just because Lovecraft or “Call of Cthulhu” say madness happens one way doesn’t mean players can’t look for another way to roleplay horror.

If there’s any part of the game that’s less than useful, it’s probably the section on Lovecraftian poetry. Why is there a chapter on Lovecraftian poetry in a roleplaying game? I do not know. The poems don’t seem bad, and the whole chapter is fairly short — but it’s also very skippable.

But on the whole, if you’re looking for a new kind of horror roleplaying and storytelling experience, one that emphasizes creeping terror and allows players to avoid the moral weaknesses of Lovecraft’s tales, this is a game you may want to try out.