Politics in Comics: Watchmen

This is the first in an occasional series I’d like to do covering politics in comics. True enough, many comics are perfectly happy to limit themselves to good vs. evil fisticuffs, but every once in a while, a comic comes along that wears its political opinions on its brightly-colored spandex sleeve. They’re often (but not always) some of the best and most interesting comics out there, and they often manage to entertainingly infuriate people who tend to get entertainingly infuriated by political matters.

Let’s get things started with a comic that’s widely considered the best ever made.

The classic 1986-87 miniseries “Watchmen” is the main reason that Alan Moore is currently acclaimed as the best writer in comics. His epic DC series follows a number of costumed vigilantes, including the sadistic, doomed Comedian, the mad, enigmatic Rorschach, the intellectual but naïve Nite-Owl, and the inhumanly powerful and usually completely nekkid Dr. Manhattan, as they investigate a number of strange crimes in a world teetering on the brink of nuclear annihilation.

Moore wrote “Watchmen” with the express purpose of dragging comics out of the often-juvenile ghetto they’d been relegated to. His success won him worldwide fame, plunked the comics genre into a decade-long “Dark Age” when gritty realism reigned, and earned “Watchmen” a reputation as one of the Best Comic Series Ever.

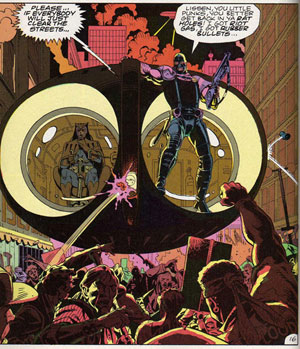

“Watchmen” is a series grounded in politics — Moore wanted his series to be more realistic than the typical long-underwear comic, so he gave his “costumed adventurers” a weakness that most people are vulnerable to: the law. In Moore’s continuity, the Keene Act was passed in 1977 and banned costumed vigilantes. Most of the nation’s heroes retire, with the exception of government agents like the Comedian and Dr. Manhattan, and Rorschach, who just plain refuses to obey.

Nite-Owl and the Comedian try to quell a riot

On top of that, the existence of government agents as brutal as the Comedian and as awesomely powerful as Dr. Manhattan cause major changes in world events. Dr. Manhattan is able to win the Vietnam War almost single-handedly — a victory that allows Richard Nixon to repeal the 22nd Amendment. In “Watchmen,” Nixon has been President for five terms.

Most notably, the comic examines how political biases would determine coverage of costumed vigilantes in the media. “Nova Express,” a glossy liberal news magazine, campaigns against vigilantes and derides them as hyper-violent fascist stormtroopers. The hard-right “New Frontiersman,” on the other hand, is an enthusiastic supporter of costumed vigilantes, depicting them as the world’s elites, society’s only hope of surviving everything from communist subversion to juvenile delinquency.

Who watches the weirdies in the colorful spandex?

So are the heroes liberals or conservatives? Yes and no. Rorschach is definitely conservative and a big fan of the “New Frontiersman,” and the Comedian is an enthusiastic government operative. But they don’t entirely pass muster as political heroes — the Comedian is a thug and not much else, and while Rorschach has a great deal of cool, the dude’s also nutty as a bag full of walnuts. Ozymandias is a very wealthy capitalist, but he’s the owner of the left-leaning “Nova Express” — and his actions at the end of the book won’t endear him to many liberals out there. Nite-Owl and Silk Spectre both come across as somewhat squishy liberals. The only truly apolitical character in the story is Dr. Manhattan, and he’s not only the most powerful person in the world, he’s pretty darn close to being a god. He’s the cold, emotionless universe made flesh, and he cares not one bean for which party is running the country.

It seems to me that, though they may have political opinions, very few of the characters in “Watchmen” have consistent political opinions. In that, they are like most of us — caring passionately about some things, violently opposed to others, but mostly untouched by the crude politics that are supposed to run the world.

In the end (hopefully no spoilers here), the entire story turns on seemingly eternal political questions: Do the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few? What is the line between terrorist and hero? Can an elite few decide the fates of the masses? Do the ends justify the means?

Everyone seems to think those are easy questions. In “Watchmen” – and in much of real life – they aren’t. Conservatives may find themselves unexpectedly favoring stereotypically liberal points-of-view, and vice versa.

“Watchmen” provides no easy answers to those questions. That’s an exercise left to the individual reader.