A friend of mine suggested recently that I should spend more time here recommending writers and artists worth reading. Fair ’nuff — there are a lot of wonderful creators out there, and it’s always a good idea to steer people toward the Good Stuff.

So let’s start with the Best of the Best: Alan Moore.

Moore is a shaggy, shaggy Englishman, a practicing magician, a worshiper of a Roman snake-god called Glycon, and the second-best-known comics creator in the world, after Stan Lee. He’s known for intricate plotlines, razor-sharp characterizations, and scripts so detailed, a single panel description can go on for a page or more.

Moore has always worked to create comics for adults. That means there’s violence, nudity, swearing, and other stuff that parents may not want their kids getting their hands on. Moore sees the comics medium as something that shouldn’t be mired in juvenilia, though he also recognizes that superhero comics can be a great deal of fun for grown-ups as well as kids.

Here’s some of his best stuff, with short descriptions.

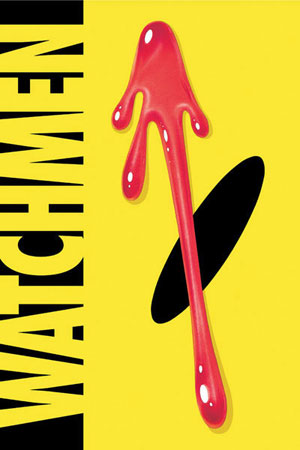

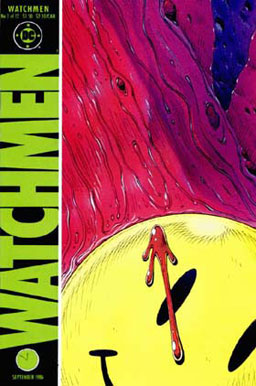

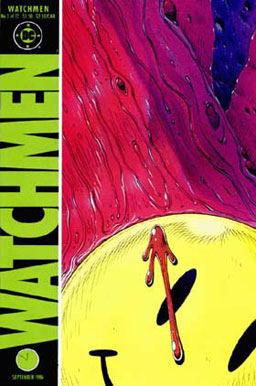

Watchmen

We’ve discussed this a bit already. This is widely considered to be the very best comic book ever created. They teach this one in many universities as literature. If you’ve never read this, you should.

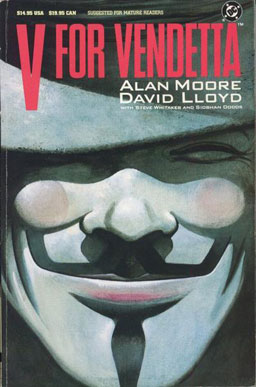

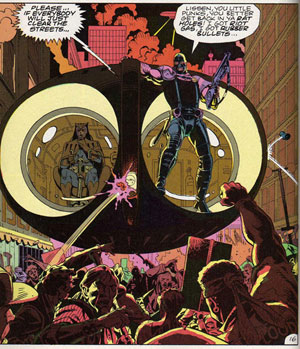

V for Vendetta

A masked, swashbuckling anarchist battles a fascist dictatorship in Great Britain. Not a perfect work — there are way too many characters to keep track of — but the story absolutely blisters the brain with excitement, derring-do, and mad, dangerous ideas. An extremely political comic — Moore wrote it in response to Maggie Thatcher’s hard-right British government.

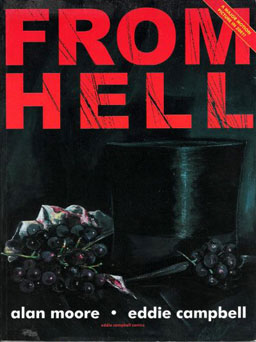

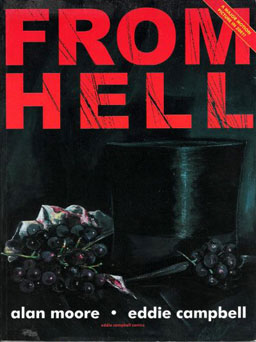

From Hell

This is a story about Jack the Ripper. Moore comes up with his own solutions for the Ripper slayings, ties it all together with head-trippy stuff about sacred geometry and time travel. Moore did a lot of research into “Ripperology” and includes an excellent bibliography and panel-by-panel endnotes. This comic is violent and absolutely blood-drenched, but if you have any interest at all in the Ripper slayings or in the seamier side of Victorian England, it’s highly recommended.

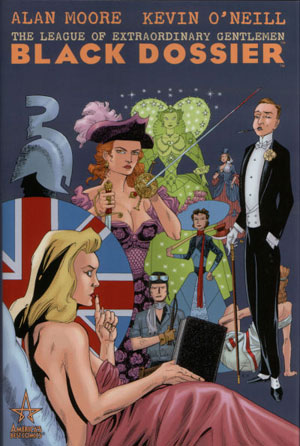

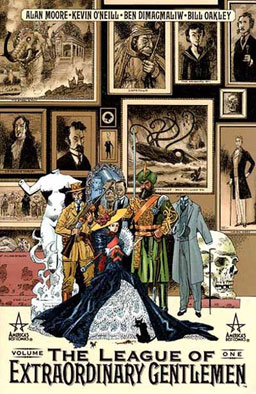

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen

It’s a superteam composed of characters from Victorian-era adventure fiction! The British government assembles a covert team of Mina Murray, Allan Quatermain, Captain Nemo, Henry Jekyll, and the Invisible Man to battle Dr. Fu Manchu. A second series of the comic has the team taking on invaders from Mars. Guest stars include everyone from Auguste Dupin, Mycroft Holmes, Dr. Moreau, the Artful Dodger, Mr. Toad, John Carter, and many, many more.

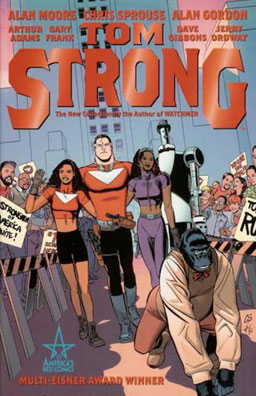

Tom Strong

A modern-day superhero book that takes most of its inspiration from old pulp adventure novels, particularly Tarzan and Doc Savage. The quality is a bit here-and-there, but in general, it’s grand, frothy fun.

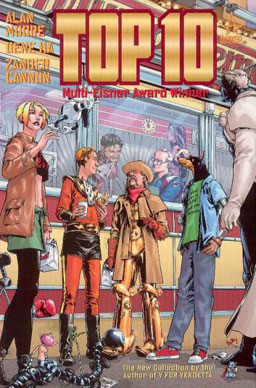

Top 10

One of my favorite Moore comics, it’s a hard-boiled police procedural set in a city where everyone — citizens, cops, crooks — has superpowers and wears a brightly-colored spandex costume. It’s a fun commentary on comics in general, plus it has a lot of really wonderful mysteries for the cops to solve. If you like TV shows like “Law and Order” or “Homicide: Life on the Street,” you’ll like this one.

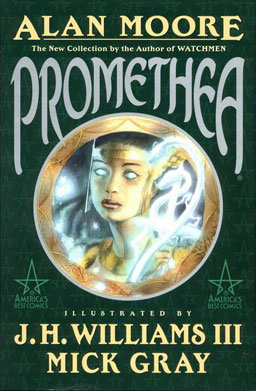

Promethea

A psychedelic/metaphysical comic about a superhero who is destined to bring about the end of the world. If you’re into new age stuff, magick, Qabalah, or the Tarot, you’ll love this. This comic is also the one where Moore does the most experimentation with visual styles and symbolism. It’s not light reading — it’s a very challenging book that requires fairly deep reading to understand.

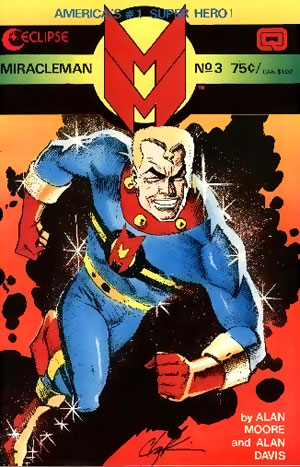

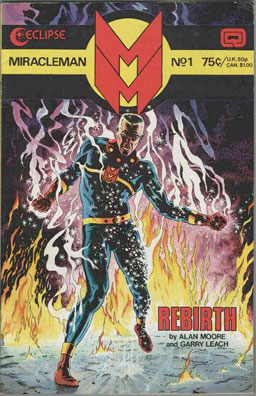

Marvelman/Miracleman

A British superhero, similar to Captain Marvel. The original version got its start in the ’50s, and Moore started working on it in the ’80s. In his version, Marvelman ends up taking over the world and ruling as a god. It’s awfully hard to find this series anywhere in the U.S. — the rights to the character and the series are in dispute. (They even had to change the name from “Marvelman” to “Miracleman” when Marvel Comics threatened to sue.)

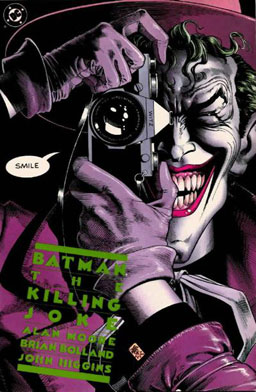

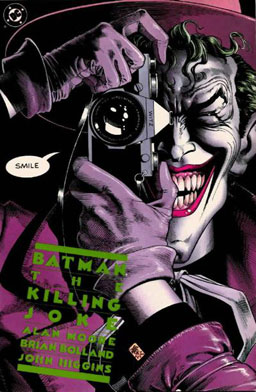

The Killing Joke

This Batman story presents the definitive origin of the Joker. And it’s the story that started Barbara Gordon on the path from being Batgirl to becoming Oracle, the wheelchair-bound super-hacker. It’s a wonderful comic, one of the best Joker stories ever.

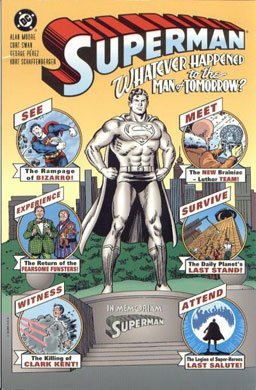

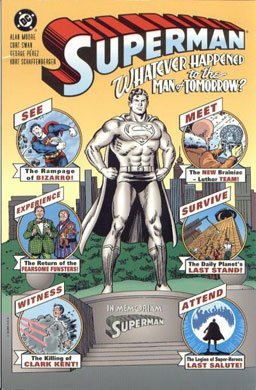

Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?

DC was preparing to reboot the Superman from the beginning back in the mid-’80s, and Moore wrote this story to bring an end to everything in the old Superman mythos. Supes is forced to deal with powerful enemies who destroy his secret identity, turn his old rogues gallery into psychotic murderers, and threaten to destroy him and everyone he loves. It’s a sad and scary story that’s soaked in nostalgia for the lost innocence of DC’s fabled Silver Age.

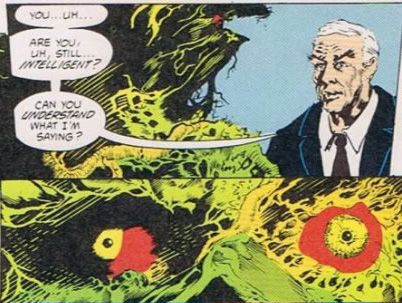

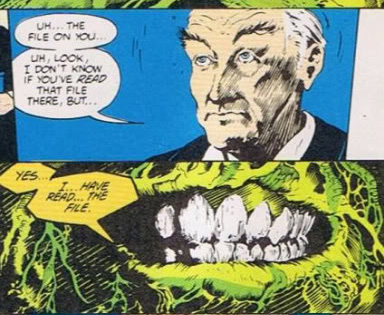

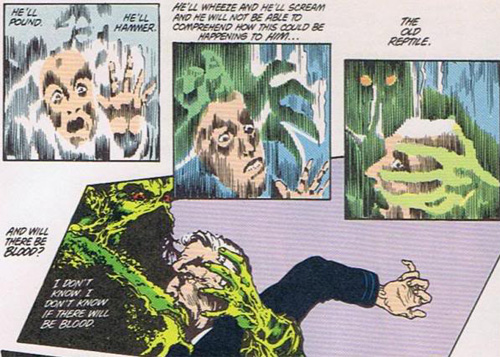

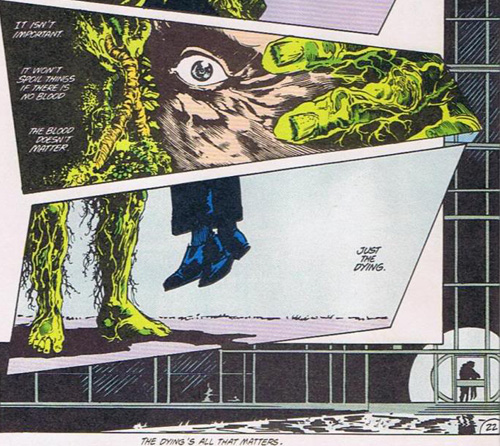

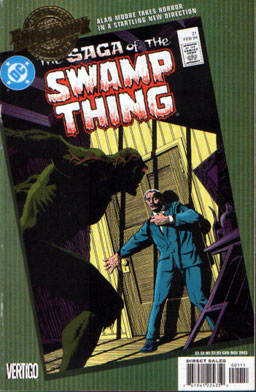

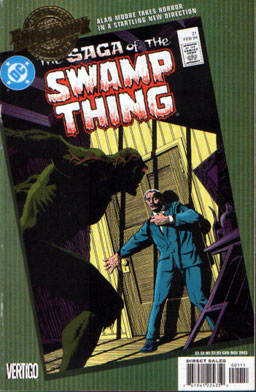

Saga of the Swamp Thing (especially “The Anatomy Lesson”)

When Moore took over this comic, the Swamp Thing was a low-selling comic on the fast track to cancellation. In the space of just a few issues, he turned it into one of DC’s best-selling and scariest comics. “The Anatomy Lesson” revamps Swamp Thing’s origin and re-introduces the character as a terrifying monster. Highly recommended — go hunt it down.

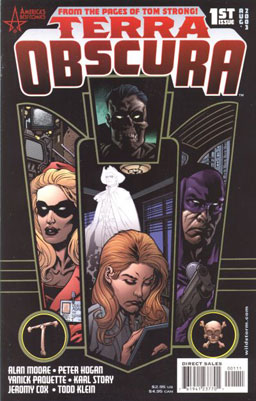

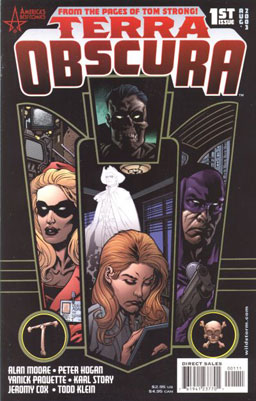

Terra Obscura

This one was just plotted by Moore, but it’s still great fun. A simultaneous spin-off from “Tom Strong” and a series of superhero comics from the ’40s, this series featured a bunch of characters with a strong Golden Age flavor but modern personalities and characterizations.

Most of these stories are still in-print in various anthologies and trade paperbacks. You can go out and buy them today. In fact, you should, because they’re all wonderful reads. Git after it, kids.